Neural Network Notes: The Basics and Backpropagation

As an individual, I feel incredibly lucky to live in an era largely free from major national or global wars, while both fundamental sciences and engineering are advancing rapidly, reaching new peaks one after another at an unprecedented pace. Among these breakthroughs, Artificial Intelligence — particularly Large Language Models (LLMs) — stands at the forefront, sparking discussions about AI, AGI, and the future of intelligence. This technology is both fascinating and revolutionary — not only because of the groundbreaking moment when LLMs first enabled fluent human-machine conversations, making what once seemed like science fiction a reality, but also due to their rapidly expanding capabilities, which have the potential to transform nearly every industry.

Out of deep curiosity, I set out boldly to understand the underlying techniques that led to these breakthroughs and to explore whether any fundamental principles of intelligence have been uncovered. But, the first step for me is to review the basics of neural networks and grasp one of the core algorithms — backpropagation. This blog serves primarily as a record of my own learning notes, rather than a comprehensive explanation on this subject.

Neural Network Basics

Briefly, a neural network is a machine learning model inspired by the structure and functioning of human brain, composed of interconnected nodes (neurons) that process sample data through weighted connections in layers, allowing it to learn and make predictions on new data. It is widely used for tasks such as image recognition, natural language processing, and so on.

Key Concepts

As what I have learned so far, the key concepts come to me include,

- Layered structure, a typeical neural network consists of the following layers:

- Input Layer: a list of neurons that can encode the information of sample data. E.g., if the sample data is an image, the neurons in the input layer will encode the values of the image pixels.

- Hidden Layers: these are the middle layers, could be one or many, and the neurons in these layers are neither inputs nor outputs. Mathmatically, they perform computations and transformations through weighted connections. And the more layers, the deeper the network (hence, “deep learning”)

- Output Layer: produces the final results. E.g. a classification label.

- Connections, each neuron in a layer is connected to neurons in the next layer through weights and biases, which can be adjusted during training process.

- Activation Function, is a function applying on each neuron in the hidden layers to introduce non-linearity, allowing the network to learn complex patterns. Common activition functions include,

- Sigmoid, historically used in binary classification problems, because it maps any input value to a range of $[0, 1]$.

- ReLU (Rectified Linear Unit), default choice for hidden layers in deep neural networks, can help learning fast.

- Softmax, used exclusively in the output layer for multi-class classification problems.

where $\mathbf{z}=(z_1, z_2, \dots, z_n)$

- Feedforward, is the process by which data flows through a neural network in one direction: from the input layer, through the hidden layers, and to the output layer. This is the foundational structure of most neural networks, where data moves forward without any loops. Mathematically, the feedforward is doing calculations at each neuron using activation function with weighted input.

- Weighted Input, $z=\mathbf{w} \cdot \mathbf{x} + b$ where $z$ is the activation of a neuron, $\mathbf{w}$ is the vector of weights connecting to that neuron from previous layer, and $b$ is the bias.

- Cost Function, is also known as loss function is a mathematical function that measures how well a neural network performs on a training dataset. It quantifies the difference between the outputs of the network and the actual desired outputs for the training dataset. And the goal of training a neural network is to minimize the cost function. One of the common cost functions is Quadratic Loss Function, also known as Mean Squared Error (MSE) or L2 Loss.

-

Gradient Descent, is the algorithm used to update the weights and biases of the neural network to minimize the cost function. The update equation for a weight $w$ is given by:

\[w \leftarrow w - \eta \cdot \frac{\partial C}{\partial w}\]$w$: the weight being updated.

$\eta$: the learning rate, a positive number controlling the step size of the update.

$\frac{\partial L}{\partial w}$, the partial derivative of cost function $C$ with respect to weight $w$. And here the cost function $C$ include the entire training dataset.

- Stochastic Gradient Descent (SGD), instead of using the entire dataset, SGD randomly selects a small subset of the dataset, called a mini-batch to compute the cost function $C$.

- Backpropagation, is the fundamental algorithm used to train neural networks. It efficiently computes the gradients of the cost function with respect to weights and biases by applying the chain rule of calculus. These gradients are then used to update the weights and biases via gradient descent, and it starts from the output layer and moving backwards to the input layer.

- Training, is the process of iteratively updating a neural network’s weights and biases to minimize the cost function until it can’t improve further.

- Epoch, an epoch is one complete pass through the entire training dataset.

- Batch, a batch is a subset of the training data used in one forward and backward pass.

- Iteration, an iteration is one forward calculation of output and backward update of weights and biases using a single batch of training data.

- Hyperparameters, these are the parameters that are set before training a neural network. Unlike the weights and biases parameter, which are learned during training, hyperparameters are not learned from the data but are chosen by the designer. They can significantly impact the performance of the neural network. Some of typical hyperparameters include Learning Rate, Batch Size, L2 Regularization Parameter, etc.

- Training Dataset, the dataset is typically split into 3 groups,

- Training Set, used to train the model.

- Validation Set, used to tune hyperparameters and monitor the model’s performance during training.

- Test Set, used to evalaute the final performance of the neural network after training.

The Architecture of Neural Network

A vanilla neural network is the simplest and most fundamental type of neural network. Its architecture can be defined as,

- Consists of input layer, one or more hidden layer, and an output layer.

- Every neuron in one layer is connected to every neuron in the next layer (fully connected layers).

- Data flows in one direction - feedforward, from input to output, with no loops.

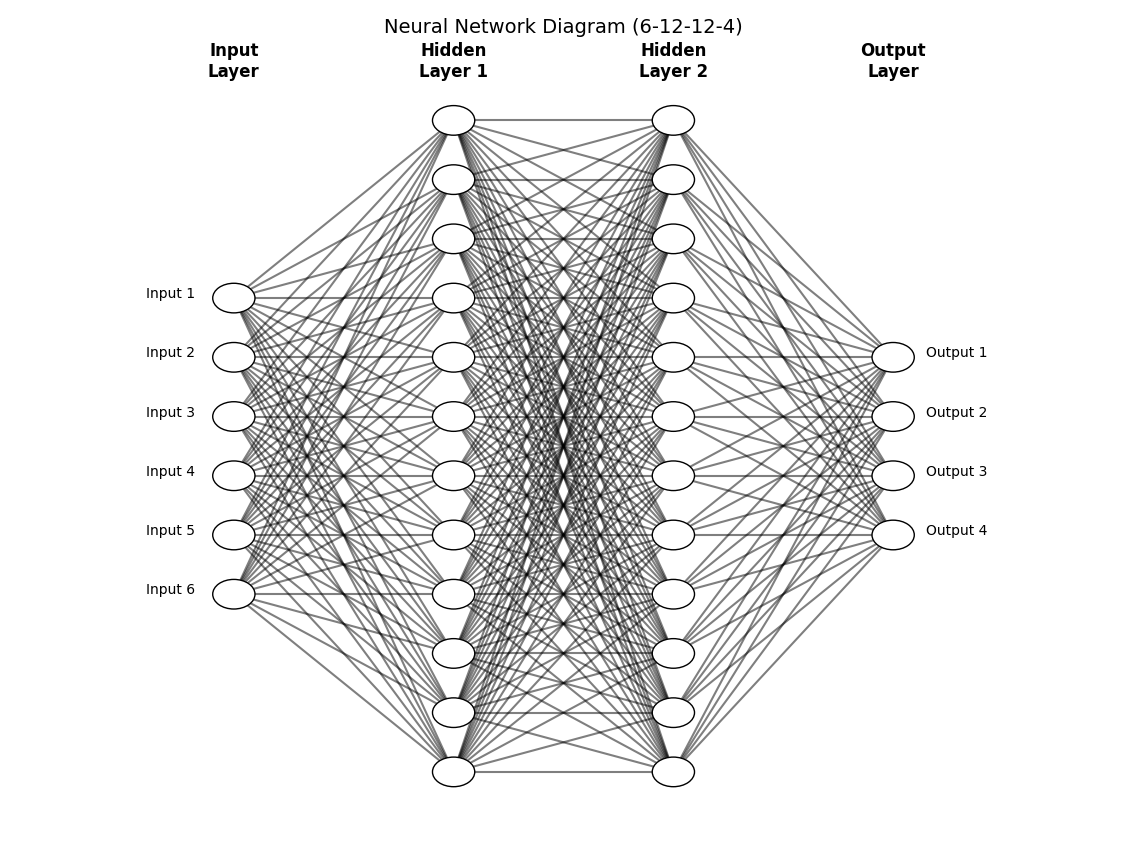

And below diagram illustrate this architecture,

Learning with Gradient Descent

Now, we have a basic neural network as illustrated above, then how can it learn from training dataset and predict well enough on new data input? The goal of the training process is to find the weights and biases so that the output from the network approximates the expected output y for all training dataset input x. To quantify how well we can achieve this goal, we can define the quaratic cost function,

\[\begin{eqnarray} C(w,b)=\frac{1}{2n} \sum_x \| y(x) - a\|^2 \end{eqnarray}\]where, $y(x)$ is the expected output vector and $a$ is the vector of outputs from the network for input $x$. And the cost $C$ is the average of the sum over all $n$ training dataset. The additional coefficent $1/2$ is mainly a convenience for cancelling out the multiplication of number $2$ after derivative.

Then, the goal of the training is to minimize this cost function so that $C(w, b) \rightarrow 0$. The good news is that this cost function is a smooth or continous function which making small changes in the weights and biases can get effective improvement in the cost. And the changes of the cost with respect to small changes to $w$ (biases $b$ is the same) is given by

\[\Delta C \approx \nabla C \cdot \Delta w\]where, $\Delta w = (\Delta w_1,\ldots, \Delta w_m)^T$ is the vector of changes made to each weight, $\nabla C$ is the gradient vector with respect to weights,

\[\begin{eqnarray} \nabla C \equiv \left(\frac{\partial C}{\partial w_1}, \ldots, \frac{\partial C}{\partial w_m}\right)^T \end{eqnarray}\]And in order to guarantee the changes to the cost $\Delta C$ is negative so that the cost $C \rightarrow C’=C+\Delta C$ can decrease properly, we can choose the small changes to each weight to be,

\[\begin{eqnarray} \Delta w = -\eta \nabla C, \end{eqnarray}\]where $\eta$ is the learning rate, defining the size or step of the move for a single update for the weights (or biases).

Then, update each weight by this equation,

\[\begin{eqnarray} w \rightarrow w' = w-\eta \nabla C. \end{eqnarray}\]Repeat this update until the cost approximately converge to zero or can’t improve further.

In summary, the gradient descent can be viewed as a way of taking small steps in the direction which does the most to immediately decrease $C$.

Backpropagation

Until now, we saw neural network can learn their weights and biases using the gradient descent algorithm. But how to compute the gradient efficiently is what Backpropagation algorithm come into play.

Some Preparations

A Matrix-Based Approach

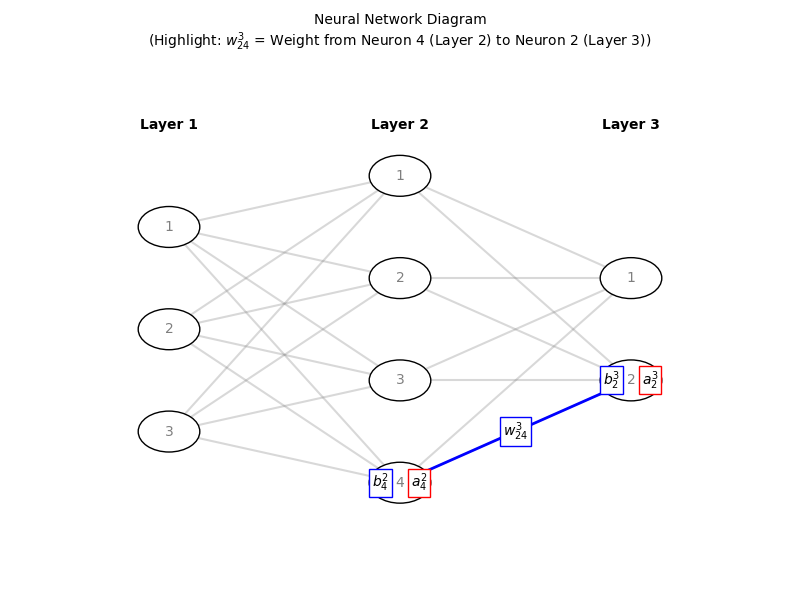

We need an unambiguous way to mark each weight on the connection from neurons in previous layer to neurons in next layer. And the convention is to use $w^l_{jk}$ to denote the weight for the connection from the $k^{\rm th}$ neuron in the $(l-1)^{\rm th}$ layer to the $j^{\rm th}$ neuron in the $l^{\rm th}$ layer. Similarly we use $b^l_j$ for the bias of the $j^{\rm th}$ neuron in the $l^{\rm th}$ layer, and we use $a^l_j$ for the activation of the $j^{\rm th}$ neuron in the $l^{\rm th}$ layer. See diagram below shows a specific weight, related biases and the activiations.

Then with these notations, the activation $a^{l}_j$ of the $j^{\rm th}$ neuron in the $l^{\rm th}$ layer is related to the activations in the $(l-1)^{\rm th}$ layer by below equation (here we use the sigmod activation function)

\[\begin{eqnarray} a^{l}_j = \sigma\left( \sum_k w^{l}_{jk} a^{l-1}_k + b^l_j \right) \end{eqnarray}\]where the sum is the over all neurons $k$ in the $(l-1)^{\rm th}$ layer. Then, we could write the weights connecting from $(l-1)^{\rm th}$ layer to $l^{\rm th}$ layer as weight matrix $W^l$. Similarly, for each layer $l$ we define bias vector $b^l$, and finally the activations of neurons in the $l^{\rm th}$ layer can be defined as vector $a^l$. The above equation can be rewritten in the compact vectorized form,

\[\begin{eqnarray} a^{l} = \sigma(W^l a^{l-1}+b^l) \end{eqnarray}\]From the matrix representation of the weights, you can now see why the notation for an individual weight follows the order of the indices $j$ and $k$. This ordering reflects how the weight matrix left-multiplies the activation vector from the previous layer.

Regard The Neural Network as a Giant Composite Function

The neural network can be considered as a giant composite function. This is a fundamental way to mathematically understand neural network. A neural network stacks multiple layers of simplier functions (neurions) to form a nested composition of functions. In a simplified form, for a network with $L$ layers, the output $y$ is computed as:

\[\mathbf{y} = f_L \left( f_{L-1} \left( \dots f_1(\mathbf{x}) \dots \right) \right)\]For a more detailed representation with respect to weights ($W$), biases ($b$), and activation functions ($\sigma$):

\[\mathbf{y} = \sigma_L \left( \mathbf{W}_L \cdot \sigma_{L-1} \left( \mathbf{W}_{L-1} \cdots \sigma_1(\mathbf{W}_1 \mathbf{x} + \mathbf{b}_1) \cdots + \mathbf{b}_{L-1} \right) + \mathbf{b}_L \right)\]It will be mind-blowing to ponder how giant this composite function could be, determined by the depth and width of the neural network.

- Depth: modern networks can have hundreds of layers - deep neural network.

- Width: each layer may container thousands of neurons.

Then, it could produce millions or even billions of weights and biases that could be adjusted through the training to fine-tune the behavior of the giant composite function. And one of the good properties of this composite function is that it is differentiable (if the activation functions are), which make it possible to learn with gradient descent and use the backpropagation algorithm to fast calculate the gradient.

Chain Rule of Calculus

Before we dive deep into the actual backpropagation algorithm, I’d like to highlight the chain rule of calculus, which is the foundational mathematical principle that makes backpropagation possbile in neural networks.

Mathematically, the chain rule of calculus can be described as: given a composite function $h$ of 2 differentiable functions $f$ and $g$, such that $h(x) = f(g(x))$, then the derivative of $h$ is calculated as,

\[h' = f'(g(x)) g'(x)\]Then, to remind again the goal of the training of the neural network is to adjust each weight and bias by a small step towards the gradient descent direction. And the key is to calculate the partial derivative of the cost function with respect to each weight and bias. The chain rule breaks this derivative into “composite” parts:

\[\frac{\partial C}{\partial W^l} = \underbrace{\frac{\partial C}{\partial a^L}}_{\text{Loss gradient}} \cdot \underbrace{\frac{\partial a^L}{\partial z^L}}_{\text{Output activation}} \cdot \underbrace{\frac{\partial z^L}{\partial a^{L-1}}}_{\text{Linear transform}} \cdots \underbrace{\frac{\partial a^{l+1}}{\partial z^{l+1}}}_{\text{Hidden activation}} \cdot \underbrace{\frac{\partial z^{l+1}}{\partial a^l}}_{\text{Linear transform}} \cdot \underbrace{\frac{\partial a^l}{\partial z^l}}_{\text{Activation derivative}} \cdot \underbrace{\frac{\partial z^l}{\partial W^l}}_{\text{Weight gradient}}\]Where $L$ is the output layer, $l$ is the index of hidden layers. Then, the key components in this equation:

- $\frac{\partial C}{\partial a^L}$: partial derivative of cost function w.r.t output activations.

- $\frac{\partial a^l}{\partial z^l}$: partial derivative of activation function of layer $l$ w.r.t the weight inputs.

- $\frac{\partial z^l}{\partial a^{l-1}}$: partial derivative of weighted input of layer $l$ w.r.t the activation input from previous layer $l-1$

- $\frac{\partial z^l}{\partial W^{l}}$: partial derivative of weighted input of layer $l$ w.r.t the weights of same layer.

Now, I think I am well prepared to dive deep into next a few sections to uncover the mathematical principles of backpropagation.

The 4 Fundamental Equations Behind Backpropagation

The below 4 fundamental equations behind backpropagation form the backbone of how neural network learn by efficiently computing gradients for each weight and bias. These equations pave the path to propagate the gradient calculation backwards through the network.

(Another notation to note first: $\odot$ to denote element wise multiplication of 2 vectors of same size.)

\[\delta^L = \nabla_a C \odot \sigma'(z^L) \tag{1}\] \[\delta^l = ((W^{l+1})^T \delta^{l+1}) \odot \sigma'(z^l) \tag{2}\] \[\frac{\partial C}{\partial W^l} = \delta^l (a^{l-1})^T \tag{3}\] \[\frac{\partial C}{\partial b^l} = \delta^l \tag{4}\]These are written in vectorized form. They can also be written in the component wise form as below,

\[\delta^L_j = \frac{\partial C}{\partial a^L_j} \cdot \sigma'(z^L_j) \tag{1'}\] \[\delta^l_j = \left( \sum_{k} W^{l+1}_{kj} \delta^{l+1}_k \right) \cdot \sigma'(z^l_j) \tag{2'}\] \[\frac{\partial C}{\partial W^l_{jk}} = \delta^l_j \cdot a^{l-1}_k \tag{3'}\] \[\frac{\partial C}{\partial b^l_j} = \delta^l_j \tag{4'}\]We define $\delta^l$ of neuron $j$ in layer $l$ by the partial derivative of $C$ w.r.t the weighted input of neuron $j$ in layer $l$

\[\delta^l_j = \frac{\partial C}{\partial z^l_j}\]and this term $\delta^l$ is also called error in the backpropagation because it quantifies how much each neuron in layer $l$ contributes to the overall cost of the network.

Then, in summary these are the purpose of the 4 equations,

- Equation (1): calculate the error - $\delta^L$ in the output layer.

- Equation (2): calculate the error - $\delta^l$ in terms of the error in the next layer $\delta^{l+1}$.

- Equation (3): calculate the partial derivative of the cost w.r.t. any weight in the network.

- Equation (4): calculate the partial derivative of the cost w.r.t. any bias in the network.

Proof of the 4 Fundamental Equations

Equation 1: \(\delta^L = \nabla_a C \odot \sigma'(z^L)\)

Proof:

By definition, $\delta^L_j = \frac{\partial C}{\partial z^L_j}$

Apply chain rule to the cost function $C = f(a^L)$, given $a^L_j = \sigma(z^L_j)$ and its derivative $\frac{\partial a^L_j}{\partial z^L_j} = \sigma’(z^L_j)$

\[\delta^L_j = \frac{\partial C}{\partial a^L_j} \cdot \frac{\partial a^L_j}{\partial z^L_j} = \frac{\partial C}{\partial a^L_j} \cdot \sigma'(z^L_j)\]Write in the vectorized form: $\delta^L = \nabla_a C \odot \sigma’(z^L)$

Q.E.D.

Equation 2: $\delta^l = ((W^{l+1})^T \delta^{l+1}) \odot \sigma’(z^l)$

Proof:

By definition, $\delta^l_j = \frac{\partial C}{\partial z^l_j}$

Apply chain rule to the cost function, w.r.t. weighted inputs on all neurions in the $(l+1)^{\rm th}$ layer.

\[\delta^l_j = \sum_{k} \frac{\partial C}{\partial z^{l+1}_k} \cdot \frac{\partial z^{l+1}_k}{\partial z^l_j} \tag{5}\]📝 Notes

This step takes me quite a while to think through and figure out. Eventually, I get that the chain rule applied in this step is the chain rule for multivariable functions!

Given differentiable function $h = f(g_1, g_2, \dots g_n)$ and $g_i = g_i(x)$ (for each $i$ in $n$), then the partial derivative of h w.r.t x is shown as below,

\[\frac{\partial h}{\partial x} = \sum_{i=1}^n \frac{\partial f}{\partial g_i} \cdot \frac{\partial g_i}{\partial x}\]Further more these points also help me to reason about,

\[C = C(z^{l+1}_1, z^{l+1}_2, \ldots, z^{l+1}_K), where \, z^{l+1}_k = f_k(z^j_j)\]

- Each neuron has full connection to neurons in next layer.

- Always keep the neural network being a giant composite function in mind.

- Think the cost function $C$ depends on $z^l_j$ through every neuron $k$ in the $(l+1)^{\rm th}$ layer:

Then, apply the chain rule for this multivariable functions gives the equation above!

Next, let’s write down the formula weighted input $z^{l+1}_k$, so that we can further calcuate its partial derivative.

\[z_{k}^{l+1} = \sum_{i} W_{ki}^{l+1} \sigma(z_{i}^{l}) + b_{k}^{l+1} \implies \frac{\partial z_{k}^{l+1}}{\partial z_{j}^{l}} = W_{kj}^{l+1} \sigma'(z_{j}^{l})\]Note, the partial derivative of $z^{l+1}_k$ w.r.t $z^l_j$ cancel out all the other terms in the equation for $i != j$

Again by definition, $\delta^{l+1}_j = \frac{\partial C}{\partial z^{l+1}_j}$

Then, we substitue $\frac{\partial z_{k}^{l+1}}{\partial z_{j}^{l}}$ and $\frac{\partial C}{\partial z^{l+1}_j}$ into equation (5),

\[\delta_{j}^{l} = \sum_{k} \delta_{k}^{l+1} W_{kj}^{l+1} \sigma'(z_{j}^{l}) = \sigma'(z_{j}^{l}) \sum_{k} W_{kj}^{l+1} \delta_{k}^{l+1}\]Write the equation in matrix form:

\[\delta^l = ((W^{l+1})^T \delta^{l+1}) \odot \sigma'(z^l)\]📝 Notes

There is a caveat for the subscript notation used here on weight. It seems the confusion arises from the conventional indexing in backpropagation derivations, where k and j are often swapped across layers.

- In the feedforward process, we use k as indexing on $(l-1)^{\rm th}$ layer, and j as indexing on $l^{\rm th}$ layer.

- In the backwards propogation process, we still use j as indexing on $l^{\rm th}$ layer, BUT use k as indexing on $(l+1)^{\rm th}$ layer.

- The essense of the notation desipte the confusion is that when backwards applying this equation (propogation), the matrix of $W$ need to be transposed.

Q.E.D.

Equation 3: $\frac{\partial C}{\partial W^l} = \delta^l (a^{l-1})^T$

Proof:

Apply the chain rule to the component wise form of this partial derivative,

\[\frac{\partial C}{\partial W^l_{jk}} = \frac{\partial C}{\partial z^l_j} \cdot \frac{\partial z^l_j}{\partial W^l_{jk}} \tag{6}\]From $z^l_j = \sum_k W^{l}_{jk} a^{l-1}_k + b^l_j $, we get:

\[\frac{\partial z^l_j}{\partial W^{l}_{jk}} = a^{l-1}_k\]Note, the other terms in the sum that are not on the specific $k$ index have been cancelled out after partial derivative.

By definition: $\delta^l_j = \frac{\partial C}{\partial z^l_j}$, then substitue this and the above result back to equation (6),

\[\frac{\partial C}{\partial W^l_{jk}} = \delta^l_j \cdot a^{l-1}_k\]Write in matrix form:

\[\frac{\partial C}{\partial W^l} = \delta^l (a^{l-1})^T\]Q.E.D.

Equation 4: $\frac{\partial C}{\partial b^l} = \delta^l$

Proof:

Apply the chain rule to the component wise form of this partial derivative:

\[\frac{\partial C}{\partial b^l_j} = \frac{\partial C}{\partial z^l_j} \cdot \frac{\partial z^l_j}{\partial b^l_j} \tag{7}\]From $z^l_j = \sum_k W^{l}_{jk} a^{l-1}_k + b^l_j $, we get:

\[\frac{\partial z^l_j}{\partial b^l_j} = 1\]By definition: $\delta^l_j = \frac{\partial C}{\partial z^l_j}$, substitute this and the above result back to equation (7),

\[\frac{\partial C}{\partial b^l_j} = \delta^l_j\]Write in vector form:

\[\frac{\partial C}{\partial b^l} = \delta^l\]Q.E.D.

The Backpropagation Algorithm

Finally, we can explicitly write this out in the form of an algorithm. (I mainly quote the algorithm description from this excellent book)

- Input x: Set the corresponding activation $a^1$ for the input layer.

- Feedforward: For each layer $l=2, 3, \ldots, L$ compute $z^l = \sum_k W^{l} a^{l-1} + b^l$ and $a^l = \sigma(z^l)$.

- Error in output layer L $\delta^L$: Compute the vector $\delta^L = \nabla_a C \odot \sigma’(z^L)$ (Equation 1).

- Backpropagate the error: For each layer $l=L−1,L−2, \ldots, 2$ compute $\delta^l = ((W^{l+1})^T \delta^{l+1}) \odot \sigma’(z^l)$ (Equation 2).

- Output: The gradient of the cost function is given by $\frac{\partial C}{\partial W^l} = \delta^l (a^{l-1})^T$ (Equation 3) and $\frac{\partial C}{\partial b^l} = \delta^l$ (Equation 4).

Note, updates to weights and biases can only be applied after all gradients are computed by the above backpropagation algorithm.

\[W_{ji}^{l} \leftarrow W_{ji}^{l} - \eta \frac{\partial C}{\partial W_{ji}^{l}}, \quad b_{j}^{l} \leftarrow b_{j}^{l} - \eta \frac{\partial C}{\partial b_{j}^{l}}\]Where $\eta$ is the learning rate.

Again the key point is: All updates are applied after backpropagation completes the backward pass. This ensures gradients are calculated based on a consistent network state.

My Journey to Learn this Subject

I have to say, this is a long learning journey for me to really understand the mathematical principles behind backpropagation algorithm. Again, I am deeply grateful to be in such an era where high-quality learning resources are readily available — a privilege that has made this exploration possible. In sharing my experience, I hope it may inspires others to embark on their own learning adventures.

My background in neural networks was limited, despite having studied the subject briefly during my postgraduate studies two decades ago. So, I want to start with a vedio tutorial to give me a general overview of neural network but still with essential mathemetical explainations. Then I came aross this terrific video tutorial from Grant Sanderson’s 3Blue1Brown Channel. Grant has a remarkable talent for visualizing complex mathematical concepts, making topics like linear algebra, calculus, and computer science not only accessible but genuinely enjoyable.

The videos helped me progress quickly — until I reached the fourth chapter on backpropagation calculus. Here, I decided to pause to dive deeper into the mathematics behind backpropagation. Then, I discovered this online book - Neural Networks and Deep Learning by Michael Nielsen, recommented by Grant in the video.

Then over the next few weeks, I spare time to read through the whole book. It clearly explains the core concepts of neural networks, including certain modern techniques for deep learning and a whole chapter to talk about how the backpropagation algorithm works with enough mathematical details!

Finally, I decide to write down my notes and learings as this blog. Along the way, I used tools like ChatGPT and Deepseek to clarify some of my doubts, further refine my understanding. (Side note: I found Deepseek’s responses particularly well organized and clear for technical explanations!)

Final Words - Reflections on Learning and Intelligence

This learning journey has been profoundly fascinating to me — how a human brain strives to understand an artificial “brain” (a neural network inspired by biological systems) that learns from data and makes accurate predictions. On a deeper level, it prompts me to ponder the very nature of intelligence itself.

Two key insights have stood out so far:

- Neural networks are mathematically giant composite functions.

- They can approximate any continuous function — a property known as the universal approximation theorem.

These observations lead me to a provocative thought: Could the universe itself be viewed as a vast, computable function? If so, human intelligence might resemble a neural network’s ability to approximate this function through learning. Yet, while learning is a shared trait across species — enabling survival through adaptation — human intelligence seems unique in its capacity for proactive exploration of existence of its own. This innate curiosity, the drive to ask “why” and “how”, may well be the defining spark of human cognition.