Large Language Model Notes: Coding Transformer with PyTorch

In my previous post, I summarized my learning experience and understanding of the Attention mechanism and Transformer architecture from a high-level, theoretical perspective. Now, it is time to get hands-on.

This post records my journey of building a basic Transformer model from scratch in PyTorch. By training this model on classic Chinese texts, I aimed to move beyond theory and gain a deep, practical understanding of how Large Language Models (LLMs) are actually built and trained.

What surprised me most was the conciseness of the implementation. Thanks to the modular design of PyTorch, it is possible to build a functional, GPT-like model with only around 200 lines of code!

Where I Started

As always, I began my learning journey by seeking out the best online courses, tutorials, and official documentation. I was incredibly grateful to discover Andrej Karpathy’s Neural Networks: Zero to Hero series on YouTube. This series provides a crystal-clear, well-structured explanation of the entire landscape — from the basic concepts of neural networks and backpropagation to bigram language models, the attention mechanism, and finally, the implementation of a GPT-like Transformer in PyTorch.

Although the videos are long, Karpathy explains complex concepts in a highly concise and intuitive way. He also shares numerous coding details and tricks that are invaluable for beginners looking to get started quickly. It is also worth noting that my previous studies on neural network fundamentals laid a solid foundation, allowing me to follow his video courses closely without frequent pauses.

The Transformer Model Architecture in Detail

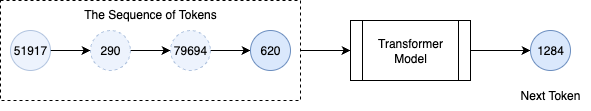

At its core and on a very high level, the Transformer model is to predict the next token in a sequence based on the preceding tokens. Simply it can be illustrated as below figure: the transformer model acts as a function that takes a sequence of input tokens and outputs the next token, and then appends the new token to the input tokens for yet another new token prediction, and so on.

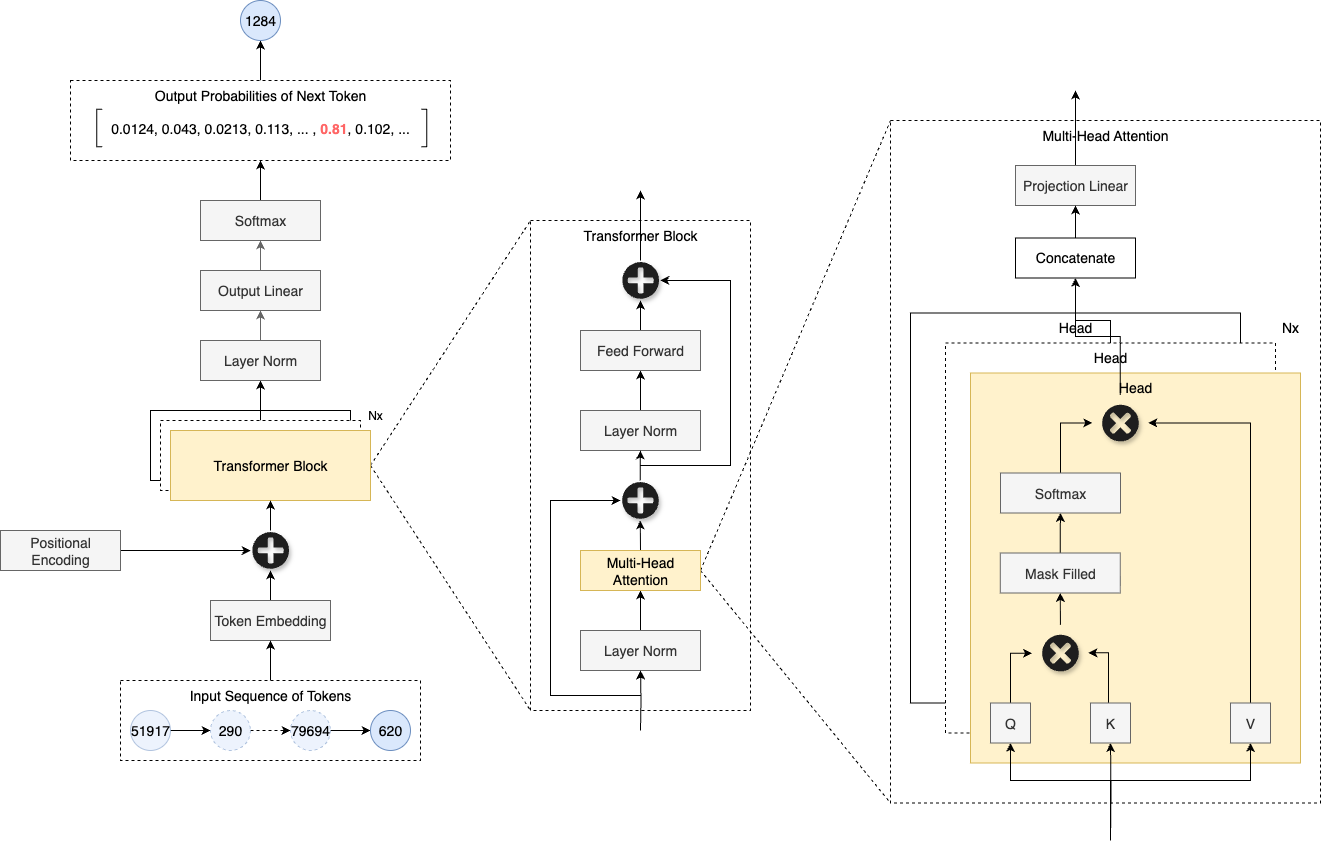

Under the hood, this is achieved through a stack of Transformer blocks, each consisting of two main components: Multi-Head Self-Attention and Feed-Forward Neural Networks, along with Layer Normalization and Residual Connections to stabilize the training process. The details of the architecture can only be better understood by diving into the code implementation, and here is a breakdown of the key components inside the Transformer model:

The code implementation of this basic Transformer model for my own education purpose can be found in my nn-learn repo, and the entire model structure shown above is implemented in just around 200 lines of code! This conciseness is possible thanks to PyTorch’s modular design, so building a Transformer becomes a matter of assembling built-in layers and classes like Lego blocks.

Here is a brief explanation of the major processing steps inside the model:

- We start with a sequence of input texts.

- The input texts are first tokenized into discrete tokens, a list of integers representing words or subwords.

- Each token is then converted into a vector representation through an embedding layer.

- Positional encodings are added to the token embedding vectors to retain information about the sequence order.

- The combined embedding vectors are passed through multiple Transformer blocks in sequence.

- Each Transformer block applies multi-head self-attention to capture relationships between tokens, followed by a feed-forward neural network to process the information further.

- Layer normalization and residual connection are used inside each Transformer block to stabilize the training process and improve gradient update flow.

- Each head in the multi-head block uses the attention mechanism to compute attention scores by scaled dot-product of queries and keys, applies a mask to prevent attending to future tokens, and then finally produces weighted sums of values based on these scores.

- Output from each head is concatenated and projected back to the embedding vector space.

- The output of the final Transformer block in the embedding vector space is projected back to the vector space of vocabulary size using a linear layer, producing logits for the next possible token.

- Finally, the logits are converted to probabilities of every possible token using softmax,

- For training, the model computes the cross-entropy loss between predicted probabilities and the expected next token, and then model parameters are updated using backpropagation and an optimizer (AdamW in this case). Besides, training is done in batches of input tokens to improve efficiency.

- For inference, the model samples the next token using Weighted Random Sampling based on its predicted probabilities.

📝 Notes (What I quoted from Andrej Karpathy’s viedo courses)

- Attention is a communication mechanism. Can be seen as nodes in a directed graph looking at each other and aggregating information with a weighted sum from all nodes that point to them, with data-dependent weights.

- There is no notion of space. Attention simply acts over a set of vectors. This is why we need to positionally encode tokens.

- Each example across batch dimension is of course processed completely independently and never “talk” to each other.

And a good explanation of the Query, Key, Value (QKV) mechanism by Karpathy:

- The Query is what you are looking for.

- The Key is what you have.

- The Value is the information you want to offer.

And this mechanism is scoped within each head.

Data Preparation and Training Results

For training the Transformer model, I chose to use some classic Chinese text as training dataset. There are 3 text files jumping into my head immediately: “Shijing”, “Lunyu”, and “Classic Chinese Poems”. It will be interesting to see how well the model can learn the structure and style of these ancient texts.

After playing with the model hyperparameters in my test function for a while, I got some preliminary test results for the 3 datasets, summarized in the table below:

| Dataset | Info | Model Configuration |

Training/ Validation Loss |

Sample Generated Text |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shijing (诗经) | Data Size: 41K chars Vocab Size: 2,835 Model Params: 0.566035M |

embd=64, head=4, layer=4, block_size=16, dropout=0.2 | 0.7709/9.0820 | 《鹿鸣之什・戎车》 不狩于堂,在城斯馆,衣日而嗟,虽则靡不夷。 |

| Lunyu (论语) | Data Size: 22K chars Vocab Size: 1,359 Model Params: 0.375631M |

embd=64, head=4, layer=4, block_size=16, dropout=0.2 | 0.6236/8.2385 | 子曰:“不教民七年,亦足恭而行之,摄乎其养;吾无求也,而其劳而不能。” 子路曰:“不得人于子荆,居室而善简,何远尔。” 曰:“举尔,知及者鲜矣。” 子曰:“吾未见刚也。” 子曰:“不好勇疾贫,不敬、冉求生之至于斯也。” |

| Classic Chinese Poems (简体中文古诗) | Data Size: 19.3M chars Vocab Size: 11,478 Model Params: 10.606294M |

embd=256, head=6, layer=6, block_size=32, dropout=0.2 | 4.4855/4.5358 | 上王丞相二首 其三 白落云昏白,青灯底黑青。 晴光下疏雨,春晖过晚凉。 老来通睡眼,目落慕别难。 快意何必虑,沧浪不受霜。 |

📝 Notes

- The test results shown in the table above are not good, even very bad for the first 2 small datasets in terms of validation loss. Further discussion on this is covered in next section.

- I didn’t spend much time on the tokenization part. I simply used character-level tokenization, treating each Chinese character as a token. This might also contribute to the poor performance on small datasets due to the large vocabulary size.

- It will not be wise and practical to train a large transformer model on CPU. For the 3rd dataset with about 10M model parameters, I used google colab with free GPU to speed up the training process. The free GPU time is limited, so not enough training iterations were done.

Overfitting and The Scaling Laws

During training, I observed that the model struggled when trained on small datasets like Shijing and Lunyu. These texts contain only tens of thousands of characters yet feature a vocabulary of several thousand unique tokens. Consequently, the model found it difficult to minimize both training and validation loss simultaneously. Regardless of the model size, the validation loss remained consistently high and began to increase after just a few thousand iterations. In contrast, the training loss continued to improve steadily as I increased the model size and training iterations.

My interpretation of this phenomenon is twofold:

- Lack of Generalization: The dataset is so small that the information within it is highly specific to the training set, making it difficult for the model to extract general patterns that apply to unseen validation data.

- Memorization: The model is too large relative to the dataset size (over-parameterized). Its excess capacity allows it to easily memorize the training examples rather than learning the underlying structure, leading to overfitting.

These observations align with the Chinchilla Scaling Laws, a set of empirical guidelines introduced by Google DeepMind in their 2022 paper, Training Compute-Optimal Large Language Models. The paper determines the optimal balance between model size and training data for a fixed computational budget. A key takeaway is that for a model to be “compute-optimal,” it is often more effective to increase the amount of training data rather than just the model size. Specifically, the paper suggests that a model should be trained on approximately 20 tokens per parameter.

Conclusion and Next Steps

I am very satisfied with this hands-on exercise. Building a basic Transformer in PyTorch, training it on classic Chinese texts, and tuning hyperparameters was a rewarding experience — even if the results highlighted the challenges of generalization on small datasets.

Throughout this process, I have found myself pondering a deeper question: Can AGI truly be achieved simply by scaling up model size and training data? How can an architecture constrained by a fixed vocabulary discover new concepts or knowledge that lies beyond the boundaries of the human language it was trained on?

These questions bring to mind the words of Ludwig Wittgenstein:

- “The limits of my language mean the limits of my world.”

- “Whereof one cannot speak, thereof one must be silent.”

- “Philosophy is a battle against the bewitchment of our intelligence by means of language.”

While I continue to reflect on these philosophical puzzles, my practical next steps will contain two paths:

- The Academic Path: I plan to dive deeper into many other advanced topics in LLMs and more mathematical and statistical foundations behind LLMs, and start reading some latest research papers to catch up with state-of-the-art developments in this fast-evolving field.

- The Application Path: I want to explore how LLMs are deployed in real-world scenarios, specifically investigating AI Agents and complex task automation. My goal is to find ideas for building AI-powered applications that can solve real problems.

Both directions are equally attractive to me. I haven’t fully decided which path to prioritize yet, but stay tuned for the next post to see where this journey leads!